What I’m Reading:

You can listen to the audio version of this Musing here.

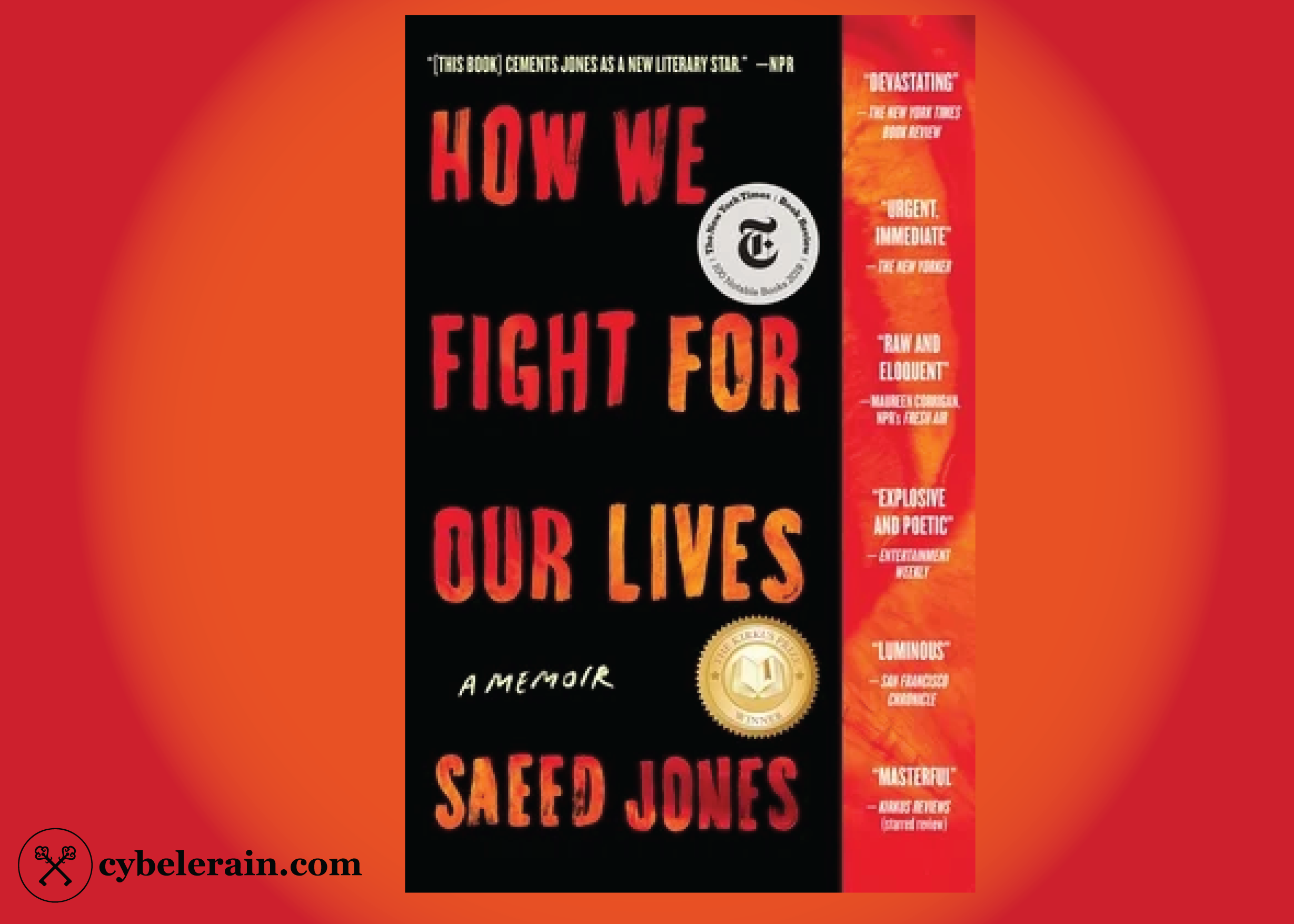

A few years ago, on a work trip to NYC, I was gifted a copy of Saeed Jones’ coming-of-age memoir How We Fight For Our Lives by a beloved client. I remember hungrily devouring the book before I made it back to Pittsburgh.

This week I decided to revisit the book (it was worth a second read!) and was pleasantly surprised to find Jones speak with nuance about a theme I’ve been thinking quite extensively about lately: coming out.

Earlier this week, I published an article on Tryst’s Blog about the impact of coming out as a sex worker. In it, I argue that while there are good reasons to come out (eg., in solidarity with other sex workers, pride, to gain political recognition as a group, to avoid the pitfalls of living a double life, etc.), the cost of doing so can be quite high, and for many workers—especially those who are multiply marginalized—it may not be worth it.

I also wrote about the ways that being out as a sex worker has come to shape my life and my relationships, and I admitted that it hasn’t been uniformly positive. Talking about this isn’t easy; as sex worker, I am always conscious to not spoon-feed ammunition to the antis, and hence, I’m inclined to hold negative experiences and feelings close to my chest.

Now while Jones isn’t a sex worker, he is a gay Black man. His memoir takes us on a journey of coming to understand himself and his (sexual) identity through and in relation to his family, white America, masculinity, and heteronormativity.

As is true with most LGBTQ coming-of-age memoirs, coming out to his family and those close to him is a key part of his journey. In a beautiful passage that points to the complexity of such an act, Jones writes,

“When I looked up, [my mother] was staring at me, wide-eyed, almost pleadingly—as if I’d led someone afraid of heights to the edge of a rusting bridge. And then I did exactly what I thought all people who love each other do: I changed the subject; I changed myself; I erased everything I had just said; I erased myself so I could be her son again.”

We know it is impossible to unsay things that have been spoken aloud, and it is precisely for this reason that coming out is so hard. Those we decide to tell cannot un-know what they come to know. But I also understand Jones’ impulse. I have sat at family dinners and pretended to be a housewife among folks who know I’m a whore for the exact reason Jones “erased” himself. I intimately know the erasure Jones writes of, it is a game we are forced to play.

What I’m Thinking About:

I argued in my Tryst piece that we don’t all have to sacrifice ourselves to the sex worker rights movement, nor do we need to feel pressure to out ourselves to those who will make our lives unsafe or unpleasant. I believe this.

And yet, my mind keeps returning to all the reasons why I continue to live the life that I do, why I continue to insist on my visibility, and why I continue to be out. Admittedly, I have the privilege of being able to do so without some of the devastating consequences that some face, but that is not to suggest that it is easy.

My hope, though (and perhaps this is too idealistic), is that those who are safe to come out will create the conditions for future sex workers to do so as well. We need only to look at Gen Z LGBTQ students who come out with a previously unimaginable specificity to know that this has been true within queer spaces. Relatedly, visibility is crux.

Jones displayed this visibly in the book when he reflected on his first experience at a drag brunch. He writes, “I didn’t need to fully understand gay culture in order for it to make me feel welcomed. All I needed to do was look around and see that gay people here didn’t appear to be scared, ashamed, hiding, or dying.” The drag queens just being out and visible to a young Jones allowed him to imagine a future for himself that didn’t include shame and fear. That is some powerful stuff.

What I’m Excited About:

Speaking of coming out (or in this case, being outed), I have been following the news story of Virginia House candidate Susanna Gibson, who was outted as being a sex cam performer on the popular site Chaturbate (interestingly, the site that started my career in sex work).

While I can’t say that I’m excited that her history of sex work is being used as a weapon to dismantle her candidacy, I am happy that instead of dropping out of the race, she has decided to fight for her rights to both do the work, and for it not to be taken out of the context it was intended for (Chaturbate). She and her lawyers are arguing that the sexual material that has been leaked was done without her consent and that this form of revenge porn should be viewed as a sex crime against her.

While I am not sure how this case will go, it does seem important. We all know that male politicians have been caught many times over hiring prostitutes and engaging in other sexual scandals. We also know that most of them go on to have relatively unscathed political careers. I have been waiting for the day when a woman who has worked in the adult industry is also the politician in question. Hopefully, this will open up a discussion about who sex workers are, why they do the work they do, and why their work in the industry should not be a barrier to other ambitions in their lives.

Booking & Availability:

Buffalo, NY | Oct 13-15

Boston, MA | Oct 26-29

Pittsburgh in between

Make sure to check out my complete travel schedule on my website.